For those who've suffered a traumatic spinal cord injury and are paralyzed, there's rarely encouraging news, which is why what's happening in early clinical trials in a research lab in Lausanne, Switzerland is so remarkable. A renowned French neuroscientist, Gregoire Courtine, and Swiss neurosurgeon, Dr. Jocelyne Bloch, have implanted a small stimulation device on the spine of paralyzed patients, helping them once again stand up and walk. What's even more surprising is their newest innovation, which uses an implant in the skull that enables patients to move their paralyzed legs or arms, just by thinking about it. When we visited their lab, NeuroRestore, in March, they were working with a 39-year-old woman whose spinal cord was severed six and a half years ago. She'd been told she'd never walk again.

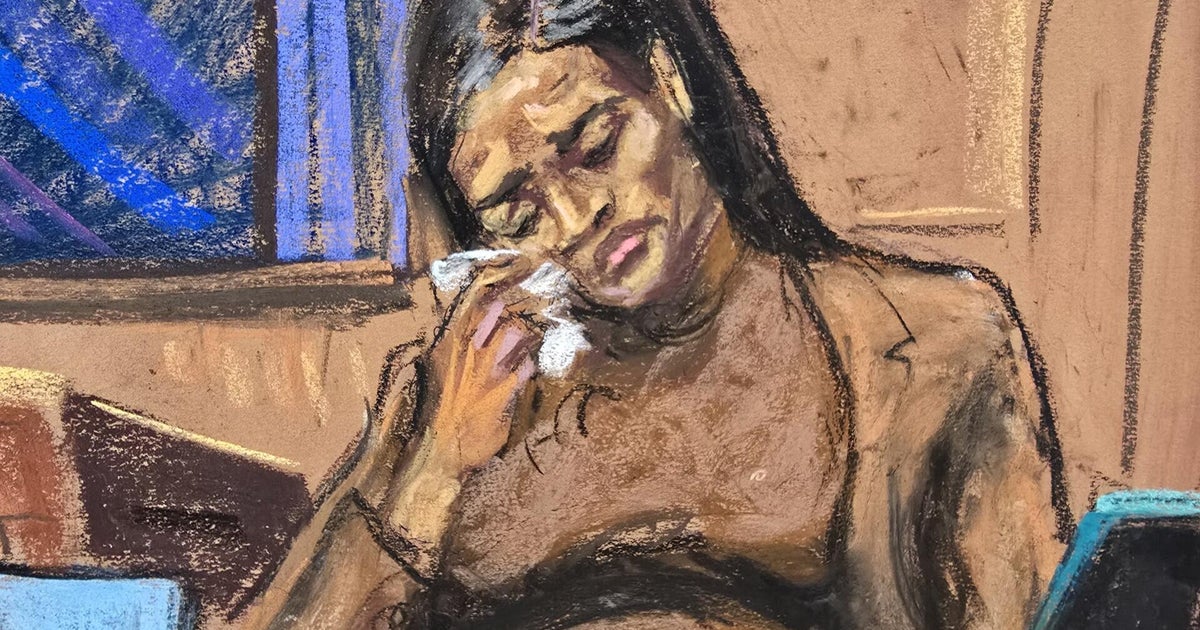

Marta Carsteanu-Dombi is the most severely paralyzed patient who's enrolled in this clinical trial at NeuroRestore to regain mobility in her legs.

She has no feeling below her waist and isn't able to keep her balance. Just sitting up on her own is a challenge.

In 2018, Marta was a new mom, working at a German tech company, when she began training with her husband for an IronMan competition. She was in the best shape of her life, but during the bike portion of the race she suffered a devastating accident.

Anderson Cooper: You were found–

Marta Carsteanu-Dombi: Near a tree.

Anderson Cooper: --near a tree?

Marta Carsteanu-Dombi: Yes. So–

Anderson Cooper: And your back hit the tree.

Marta Carsteanu-Dombi: We're hypothesizing what happened, right, 'cause nobody saw me. So, I must have had a pretty tough collision because my spine basically broke, like, two dimensions.

Marta Carsteanu-Dombi

60 Minutes

Marta Carsteanu-Dombi

60 Minutes

Her spinal cord injury was so severe doctors said there was no sign of nerve connections left to her lower body. She'd also broken eight ribs, punctured her lungs, and was bleeding internally. She needed emergency surgery and doctors told her family she might not survive.

Anderson Cooper: You came out of the surgery-- I understand you wrote a message to your mom.

Marta Carsteanu-Dombi: So the surgery took about seven to eight hours, and I was intubated; I could not talk. And my mom, you can imagine, was in tears. And I just wrote to her, "I'm strong."

That strength has been tested. Marta spent 10 days in intensive care and four and a half months in a rehab hospital learning to adapt to her new life in a wheelchair.

Anderson Cooper: Traditionally, if someone gets a spinal cord injury, what are the treatment options for them?

Jocelyne Bloch: You have to do a little bit of physiotherapy, get into a wheelchair and then you go back home. And that's all.

Anderson Cooper: That's it?

Jocelyne Bloch: That's it. And that was for many years the only option.

Dr. Jocelyne Bloch and Gregoire Courtine have been at the forefront of researchers trying to expand those options since 2012. Their lab, near Lake Geneva, is a collaboration between the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Switzerland's MIT, and the Lausanne University hospital. That's where they've implanted eight paralyzed patients with a device that allows them to stimulate their spinal cords, enabling them to stand, take steps with a walker, and lift weights. Some can even climb stairs. They use a button to activate the stimulation.

And now, thanks to Courtine and Bloch's latest technology, five other patients can move their paralyzed limbs using their own thoughts. It's called a digital bridge, and it wirelessly connects a patient's brain to their spinal cord stimulator.

Gregoire Courtine: Normally there is a-- a direct communication between the brain and the spinal cord.

Anderson Cooper: For me to walk, my brain just automatically tells my legs to walk?

Jocelyne Bloch: Uh-huh.

French neuroscientist Gregoire Courtine and Swiss neurosurgeon Dr. Jocelyne Bloch

60 Minutes

French neuroscientist Gregoire Courtine and Swiss neurosurgeon Dr. Jocelyne Bloch

60 Minutes

Gregoire Courtine: But because of the spinal cord injury the signal is interrupted. So we are aiming to bridge-- bypass the injury by having a direct digital connection between the brain and the region of the spinal cord that control leg movement.

To do that, Dr. Bloch implants a small titanium device, originally developed by a French research institute, in the patient's skull directly over their motor cortex, the area of the brain responsible for controlling movement.

Gregoire Courtine: You see you have the 64 electrodes.

Anderson Cooper: And so each of these is what?

Jocelyne Bloch: It's electrode that are recording populations of neurons underneath. And you can immediately see which one are the best correlated to certain movements.

Gregoire Courtine: Like the hip is here, and then the knee is here, and then the ankle is here, etc.

Jocelyne Bloch: Yeah, yeah.

When a patient thinks about moving a limb, those electrodes record the brain's activity. Then a computer uses artificial intelligence to translate the recordings into instructions for the stimulation device implanted on the spinal cord. That device sends electrical pulses activating muscles in the legs or arms. All of it happens in about half a second.

Gert-Jan Oskam was the first person to get the "digital bridge" four years ago after he was paralyzed in a bike accident. We met him for a walk by Lake Geneva.

Anderson Cooper: So now the stimulation is on?

Gert-Jan Oskam: Now it's on, yes.

Anderson Cooper: Do you feel it at all in your body?

Gert-Jan Oskam: I do feel a little tingling sensation from the stimulation with my brain.

Dutch man Gert-Jan Oskam can now walk up to 450 feet.

Dutch man Gert-Jan Oskam can now walk up to 450 feet.

His headpiece powers the implant in his skull, and on his walker is the computer. It's cumbersome and tiring, physically and mentally, but he can walk up to 450 feet.

Anderson Cooper: It's incredible to me though that you can continue talking with me even though this machine is reading the signals from your brain.

Gert-Jan Oskam: It's able to discriminate walking and talking at the same time. That's-- that's incredible.

Anderson Cooper: For somebody who has not been able to control their movements, to suddenly be able to control their movement, I mean, that's--

Jocelyne Bloch: Yeah. There is this initial phase of surprise, you know, when they realize that it's-- they are giving the order and it's happening. You know?

Gregoire Courtine: They are like, "Did I do that? Like, is it me or you actually stimulate it, no?" I say, "No, you did it."

Anderson Cooper: They think you're pressing a button somewhere and doing it? Jocelyne Bloch: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Gregoire Courtine: They don't understand 'cause they've been paralyzed for so many years.

Marta got the digital bridge implanted in September. She's worked with a team of engineers and physical therapists to figure out how much electrical stimulation is needed to move her legs.

Gregoire Courtine: Nice.

Marta Carsteanu-Dombi: Yeah, it's good.

Gregoire Courtine: And up.

Anderson Cooper: So that's the stimulation-- the electrical stimulation is making the leg move.

Gregoire Courtine: Yeah, Marta is completely paralyzed.

But Marta's also had to teach herself to think about moving the exact same way every time, so the AI can recognize her thoughts. She practiced at first with this avatar.

Anderson Cooper: You have to relearn or rethink how to walk.

Marta Carsteanu-Dombi: Exactly. So we were experimenting a little bit. What do I think about? Is it I think about the hip being contracted? Do I think about the knee lifting up? Do I think about the ankle?

To show us how she does that, they disconnected her skull implant from her spinal cord stimulator and connected it to this exoskeleton.

Anderson Cooper: You can control this with your thoughts right now.

Marta Carsteanu-Dombi: Yeah. If I want to do a right movement, right hip flexion, it does a right hip flexion.

Anderson Cooper: You're not pressing any buttons–

Marta Carsteanu-Dombi: No.

Anderson Cooper: --or anything. You're just thinking.

Marta Carsteanu-Dombi: Sure.

Anderson Cooper: Can you look at me without looking at it and just-

Marta Carsteanu-Dombi: Do a right one? Yes. I think it works.

Anderson Cooper: Yeah.

Gregoire Courtine: It does work.

Marta Carsteanu-Dombi

60 Minutes

Marta Carsteanu-Dombi

60 Minutes

After training with the digital bridge for just two days, Dr. Jocelyne Bloch and Gregoire Courtine, or G as Marta calls him, put her to the test- eager to see if she could take some steps.

Marta Carsteanu-Dombi: Jocelyne and G come in and it's like, "Okay, show off. So what can you do?"

Anderson Cooper: They said, "Show off?"

Marta Carsteanu-Dombi: Yeah, yeah.

Anderson Cooper: Were you ready to show off?

Marta Carsteanu-Dombi: I did not know if I'm able to show off. This was the thing.

Using a harness to support about half her body weight and physical therapists to help place her feet on the ground, Marta took her first steps. Despite having no sensation below her waist, she was able to move her paralyzed legs with her thoughts.

Anderson Cooper: What was that like?

Marta Carsteanu-Dombi: Gaining some superpower. A power that I did not have before. And now with these implants, you know, it's-- I'm a real Ironwoman.

When we were there in March, Marta wasn't able to walk on her own yet, but she said she'd already regained something she'd lost.

Marta Carsteanu-Dombi: It's giving me my perspective back. Standing up again and looking people in the eye, that's different.

Anderson Cooper: A difference in how you think about yourself or in how others see you–

Marta Carsteanu-Dombi: Both–

Anderson Cooper: --or how you interact in the world?

Marta Carsteanu-Dombi: Everything. Everything.

Arnaud Robert: You leave the hospital on your wheelchair and you notice the different looks.

Anderson Cooper: Right away you noticed?

Arnaud Robert: Yeah. Scared looks. Also, a lot of smiles that are a little bit too long.

Arnaud Robert

60 Minutes

Arnaud Robert

60 Minutes

Those well-meaning smiles reminded Arnaud Robert, who's quadriplegic, how much his life had changed. A Swiss journalist, he'd spent decades traveling the world, but three years ago he slipped on a patch of ice and was instantly paralyzed from the neck down. He regained some function in his right arm with physical therapy, but wanted to see if the digital bridge could help him with his left.

Anderson Cooper: Opening and closing the hand is far more complex than walking?

Gregoire Courtine: It is, because of the possibility to access a different muscle individually.

Jocelyne Bloch: The hand is tricky with all these different little muscles. It's very subtle.

But after surgery and training at Courtine and Bloch's lab for eight months, he was able to use his left hand to help hold a glass and type.

Arnaud Robert: Even to be able to move my fingers, this is something that I couldn't do. And, of course, moving the-- the arm like that, this is something that I couldn't do either.

Anderson Cooper: That's incredible.

Arnaud Robert: It's really incredible. I mean, I don't want to pretend that I'm using this left arm on a daily base. There is a long, long way to get it functional for every quadriplegic in the world. But it was certainly a success, because I see that I can do things that I wouldn't-- I was not able to do before.

But something else has happened as well: after using the digital bridge over time, both Arnaud and Gert-Jan have improved their ability to move their paralyzed limbs, even when the system is turned off.

Anderson Cooper: How is that possible? What happened?

Jocelyne Bloch: That was also our questions. And we could not do much in a human being to understand it.

Since it wasn't possible for them to see the changes in their patients' spinal cords at a microscopic level, they did studies in animals to understand what was happening.

Gregoire Courtine: What we understood was completely unexpected, that this training enabled the growth of new nerve connection. So new nerves started growing. And they grow on one very specific type of neuron that is uniquely equipped to repair the central nervous system.

Jocelyne Bloch: So we also observed that the less the severity of the spinal cord lesion is, the, the better the regrowth happens. You know? If it's a complete spinal cord injury, it will be hard to regrow. But, indeed, there is something happening.

How well the digital bridge works still needs to be studied in a lot more patients. They hope to launch clinical trials in the U.S. in the next two to three years. The FDA has already designated it as a breakthrough device, which will prioritize the review process, and Courtine and Bloch have co-founded a company called Onward Medical to bring this technology out of the lab, making it faster, smaller, and widely available.

Marta Carsteanu-Dombi: It's not changing my everyday in ways people might think, "Oh, she's-- she's getting back her life she had before." So as long as it makes me feel good, that I can stand up and hug my husband or hug somebody that I love, that means a lot.

Anderson Cooper: What's your goal?

Marta Carsteanu-Dombi: To go out in the park, and just stand up and do some steps with my family. It's not a stroll in the park how it would look for most other people. But for me it's just good enough to make me happy.

After six months of hard work, just before Marta was to return to her family, she did what doctors years ago told her she never would: she took a few steps. No harness to hold her, just her walker and her iron will.

Produced by Nichole Marks. Associate producer, John Gallen. Broadcast associate, Grace Conley. Edited by Peter M. Berman.

Anderson Cooper